WHY SET A BOSNIA NOVEL IN PARIS?

When I started writing This He Did Without Remorse several people asked me why I’d chosen to set it in Paris. Since much of the plot turns on the fallout from events which happened in Bosnia, wouldn’t Sarajevo have been a more obvious choice of location? Perhaps. Except the book isn’t really about Bosnia, it’s about the impossibility of leaving places behind, and how you might think you can leave your homeland, but in truth you always carry it with you.

When I started writing This He Did Without Remorse several people asked me why I’d chosen to set it in Paris. Since much of the plot turns on the fallout from events which happened in Bosnia, wouldn’t Sarajevo have been a more obvious choice of location? Perhaps. Except the book isn’t really about Bosnia, it’s about the impossibility of leaving places behind, and how you might think you can leave your homeland, but in truth you always carry it with you.

I say this as someone who left her home and native land twenty years ago, and has lived in Scotland, France and England since then. When I arrived in the UK I was still young enough to quickly find my feet, and that elusive sense of inclusion which lulls you into thinking you actually do belong. I soon felt as at home in Glasgow as in Montreal, and was quite taken aback somewhere around year four, when I went ‘home’ for a visit only to find myself a stranger in a strange land. Again, I was young enough at the time that this didn’t worry me, but it did leave me feeling like I was outside my life, looking in a lot of the time. When I moved to France in the mid-90s, I felt a similar assimilation experience, and found myself genuinely torn between there and Scotland, with Canada no longer really feeling part of my emotional equation. Over the years, as is often the way of the long-term expat, my circle of friends came to resemble a UN committee. I was rootless and fancy-free, and this didn’t worry me in the slightest. It wasn’t until I married someone whose roots were planted centuries deep that it finally hit me that not only would I not be going home again, but the so-called ‘home’ in my head no longer even exists.

Questions of identity were weighing heavily on me, and yet I could hardly have written a novel about my own experience. Imagine the blurb: Young woman from safe, affluent country moves to yet another G8 hotspot, before trying her hand at a third. Instead, I did what writers have done for centuries. I took my own pre-occupations with cultural and personal identity and gave them to characters for whom they could be matters of life and death. It’s for this reason that This He Did Without Remorse is inhabited by people who have been violently uprooted from their own culture, as well as others who can trace their lineage back many generations in the same square kilometre, and a few who are in transit between the two.

This still doesn’t quite explain why Bosnia, or why Paris, specifically.

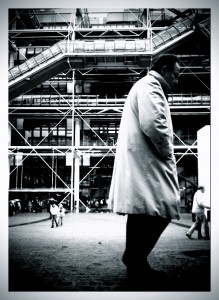

The Paris part is simple. Firstly, I chose to set this novel there because in my heart, all roads lead to Paris. Secondly, because from the start I knew questions of identity were going to be paramount, I wanted the background culture to be one where there was a disproportionately passionate, and yet ultimately benign, sense of national identity. Most French people I know believe their way of life is demonstrably better than yours/mine/anyone else’s. But they’re not really interested in taking up arms to persuade you of it. Thirdly, in any police procedural series, it’s only a matter of time before the detectives have to contend with the war criminals coming to town. Since this dovetails so neatly with other forms of migration in the book, it made sense to me to start with this book.

Why Bosnia? As I said above, I was looking for a place where questions of cultural identity could potentially be a matter of life or death. I also wanted a character who would be trying to take a sort of distance-learning approach to integrating into what she believed to be her true culture. It struck me then that she should be from a culture I would also have to study as an outsider. But neither could it be something entirely alien. Having read Balkan literature (in translation) and seen films set there, and/or about there, it struck me as both very foreign, and yet highly recognisable. I was brought up in Quebec, in a time of political tension over what appears on the surface to be a trivial cultural divide: what language do you speak? When I first arrived in the UK, Quebec Independence was still a hot political topic, and people used to ask me, but what is it actually all about? From the outside, the notion of political emnity based on a language divide seems completely absurd. And yet, during this time, the Troubles were still in full swing, and in Quebec, people were asking themselves, but can they possibly be planting bombs over a religious divide? Recently, I spent a day at the public library in Lisburn, where they have an extremely moving exhibition of photographs from the Troubles. Looking at those photos, I couldn’t help feeling how fortunate I was to have been born into a cultural divide where the two sides of a seemingly arbitrary political battle at least managed not to let their animosity drag them into widespread violence. Of course, when ethnic cleansing began in the Balkans, not only was there wanton loss of life on all sides, but civilian populations had to endure the added tragedy of systematic rape. This also contributed to my decision to have several of the characters come from this region. For having grown rather bored of crime novels in which serial killers drag young female victims to their maniacal lairs to chop them up, I wanted to write a police procedural series with a more rounded view of crimes perpetrated against women and children.

The result of all this has been This He Did Without Remorse, a story of identity, belonging, and how confronting the past can set you free.