My grandmother’s hundred and fifteenth birthday.

This passport, issued by the Foreign Office on the 21st of May 1919, belonged to my Grandmother. It records her name as Jacqulin, but I rarely ever heard anyone use it. She was always Mum or Gran or Granny by the time I arrived on the scene. She once told me her husband, the grandfather I never met, always called her ‘Lina’. She laughed coyly then, and anyone could see she had loved being called Lina. Loved him.

This passport, issued by the Foreign Office on the 21st of May 1919, belonged to my Grandmother. It records her name as Jacqulin, but I rarely ever heard anyone use it. She was always Mum or Gran or Granny by the time I arrived on the scene. She once told me her husband, the grandfather I never met, always called her ‘Lina’. She laughed coyly then, and anyone could see she had loved being called Lina. Loved him.

It doesn’t say where this document was issued, but my guess is Edinburgh, where she was living by 1919.

There are so many things I love about this passport. Not only is the photo stuck on with a bit of glue, but what a photo it is. Taken against a backdrop of painted trees, with its smiling young raven haired beauty (Granny once had long, dark hair?!), it could be a scene from Ivanhoe, or Brigadoon. I like to imagine her arriving at Ellis Island, or Halifax (she made the ocean voyage twice in her lifetime) and having the immigration officer ask her to turn to one side so they could verify her profile.

Gran died twenty-five years ago, while I was living in Edinburgh, as it happened – but had she lived, today would have been her 115th birthday. She was in her 90th year when she died, still living at home, alone, looking after herself until the last.

Jacqulin was fiercely independent. So much so that, in her later years, the minute she finished a cup of tea, she would leap up and wash it. A few years before she died, I teased her about this cleaning mania. I discovered that, on turning eighty, she’d adopted a policy of doing everything now – in case she died suddenly and couldn’t get to it later. So she washed her dishes the minute she finished eating, and even confessed to hand-washing her knickers every night, hanging them to dry before going to bed, because she couldn’t face the thought of anyone else having to clean up after her. I laughed and told her not to worry, that if she ever did die I’d be sure to throw away her knickers when no one was looking.

She stopped and stared, speaking firmly. There was no *if* about it, she definitely was going die, so I should start getting used to the idea. It was a theme she would return to. In the spring of 1987, I rang her to say I’d booked a flight to Montreal for Christmas that year. That’s nice, she said, but I won’t be here. For a minute I thought she meant she’d be going to Toronto to her youngest son’s place. But then she explained. By Christmas, she wouldn’t be here at all. I told her to stop this, that she knew I hated that kind of depressing talk. She snapped back that I wasn’t listening, and that we weren’t going to see each other again, and that it would be better for me to start getting used to the idea as soon as possible. Unfortunately, I can no longer remember how the call ended, but I do know it was the last time we spoke.

As counsel goes,’get used to the idea that loved ones die’ is both excellent and impossible. But then, giving advice which could withstand simmering was one of Gran’s great fortes. My favourite example was dolled out when I was perhaps fourteen or fifteen years old. Having had the perplexing benefits of a Catholic upbringing, I asked Granny if she really believed you had to wait until you were married before having sex. She shook her head. No, she said, but you have to think about it like this: if I have sex, I’ll probably get pregnant, and if I get pregnant, I’ll probably have a baby. Then, one day, that baby will grow up and be old enough to turn around and ask, what in God’s name possessed you to saddle me with him as a father? At which point, I’d need to have a better answer ready than, Och, you should have seen him dancing!

Sadly, she was long gone before I properly understood the true value of this advice. I wish she had lived long enough to meet my eventual husband, because I think they’d have got on like a house on fire. But more than this, I know she would have been thrilled to bits to meet her great-grandchildren. A few weeks ago, my nephew found a box of home-movies from forty odd years ago in his parent’s garage. I suddenly remembered exactly the reels he was talking about, and that there would be footage of our grandmother from when we were all babies. I could hear this really had no meaning at all for him. His own grandparents are such an enormous part of his life, and he and his sister of theirs, but, at thirteen, he is not yet old enough to see the value of films that go back three generations.

This is the way of things. I see this now, and my grandmother saw it long before I ever did as, no doubt, did hers before us. Maybe one day, fragments of our conversations will come back to my nephew. I like to picture him, sitting on his yacht in the Med, thinking about that mad old auntie who once tried telling him something about his great-grandmother and some film playing in reverse so that everyone looked like they were jumping out of the swimming pool instead of in to it. His brow will wrinkle then, as he wonders what the hell her point could have been. But, of course, it’ll be too late.

I suppose I could always try and warn him to start getting used to the idea now, but worrying about all the shocks to come still strikes me as cripplingly depressing.

Jacqulin was born in the late 19th century, and lived until the late 20th. This means she was walking around with full-colour memories of both the Victorian era and the moon landings. I often think about this when anyone mentions how quickly things are changing in our lifetime. It strikes me that while yes, I get a new phone with boggling features I never really use every year or so, the idea of phone itself isn’t actually all that new to me. My iPad is totally amazing, but it is still only really a progression on the idea ‘computer’ which, although not yet widespread, still existed when I was a child. But to go from horse-and-cart to the moon in one lifetime, well that’s a lot of change to absorb.

Gran’s cooking was one thing which never made the leap from 19th to 20th century. As a child, I found it terrifying. It seemed to consist entirely of grey things we didn’t get at home, or anywhere else, served up with an overly generous ladle. As I got older, I discovered the grey food thing is just what happens if you boil otherwise normal ingredients like lamb, kidney, or vegetables for many hours. I loved my Gran, but lived in mortal fear of having to go around to hers for Sunday lunch. Weirdly, my father and uncles all seemed to love these boiled offerings, gobbling them down and then asking for seconds, which she’d jump up to bring through, waiting on the lot of us hand and foot.

Jacqulin was a very good sport as a babysitter. She not only sat through, but also pretended to enjoy, Planet of the Apes and A Howling in the Woods with us on a black-and-white telly that was never quite tuned into the station properly. She actively encouraged sneaking out onto the snow mobiles, well into her 70s, even though my father was very clear that neither she, nor we, were allowed to use them without him there. (She would laugh at this, and tell us, don’t worry, he just needs reminding that I’m his mother.)

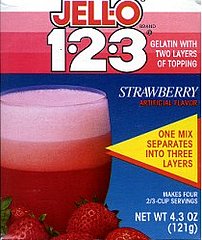

Packet food puzzled her, and I have a vivid memories of a weekend when my parents were away and I asked if she would make our latest favourite thing, Jello 1-2-3. As you can see from this photo, it’s a sort of jellied pudding thing which you mixed up and put in the fridge until it magically separated into three layers. Or, at least it did when Mom made it. But all of Gran’s attempts ended up as just one big pink fuzzy layer. This infuriated her, and I remember being despatched on my bike to go buy in more boxes until she’d finally cracked it.

put in the fridge until it magically separated into three layers. Or, at least it did when Mom made it. But all of Gran’s attempts ended up as just one big pink fuzzy layer. This infuriated her, and I remember being despatched on my bike to go buy in more boxes until she’d finally cracked it.

Another time, when I was older and more accustomed to the weird Scottish food thing, I went around to Gran’s for dinner with my then boyfriend, to find her in a complete flap. A power cut meant that long-boiled roast was no longer on the menu. Instead, Gran suggested, we would go out for Chinese food. This was surprising enough in itself. But there are no words for conveying the astonishment I felt when we walked in and half the place greeted her by name. Gran is a regular? At the Hong Kong House?

Other gems of advice Jacqulin gave me were don’t make big decisions when it’s raining, and never, ever, ever cut your hair when you’re on your period. Each have proved invaluable in their own way, and should be regularly issued to girls aged twelve and up, in schools throughout the land.

I doubt if my grandmother was quite five foot tall, but this didn’t stop her from being a towering figure in many lives. She survived her husband by a lifetime, and buried more children than anyone should ever have to. Since her death in 1987, Jacqulin’s family has continued to grow, as we’ve welcomed new spouses and children. But we’ve also suffered heavy losses, including two more of Jacqulin’s children, and one of her beloved granddaughters.

My grandmother knew a lot about love, and about loss, and passed whatever she could on with endless generosity. But despite her best advice about the theoretical possibilities of people dying, it still catches me out every time.

Anyway, Gran, this post is starting to be as rambling as that filthy joke about Rabbie Burns and the Catholic priest you made me promise I’d never tell anyone you told me. Although, to be fair, the idea of what counts as filthy nowadays is one thing that has actually changed in my lifetime. So they’re probably setting that joke to music on children’s telly as I type this. Still, my lips are sealed, Gran. Except to say, Happy Birthday, Jacqulin!

p.s. I was speaking to Ben on the phone earlier (he’s doing very well, with grandchildren of his own now) and he was just as surprised as me to learn there are no ‘e’s’ in Jacqulin.