In January, I decided that 2013 should be my year of thinking about creativity. What inspires it? What drives it? How can we tap in and harness it to enrich our lives? So I was very grateful when the producer Roland Holmes got in touch offering to let me have a Behind the Scenes chat with Director, Dan Clifton of Atomium films, who are in pre-production for an exciting new film adaptation of William Boyd’s short story ‘The Ghost of a Bird’.

Dan Clifton of Atomium films, who are in pre-production for an exciting new film adaptation of William Boyd’s short story ‘The Ghost of a Bird’.

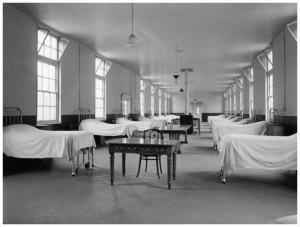

Without wishing to risk any spoilers, Boyd’s story tells of Patient 39, a young British soldier who has had his memory severely impaired as a result of a head trauma sustained in combat, outside Caen in Normandy, on June 12, 1944.

When Roland first got in touch about the project, it intrigued me on several levels. The first, is that anything with the words ‘William Boyd’ in it is a guaranteed temptation, as he has long been one of my favourite authors. Similarly, having lived in Caen for a few years, reading it there in black and white always catches my heart out. And, the thought of coming to terms with traumatic memory loss is particularly poignant to me at the moment. For the past few years I have been caring for an elderly relative who has been gradually disappearing into profound Alzheimer’s, and for whom, as Boyd says of Patient 39, ‘life has become an endless series of labyrinths.’

Although I had read Fascination some years ago, I had only the vaguest memory of ‘The Ghost of a Bird’ – no irony intended. Re-reading it, I was now able to recognise just how brilliant a representation of interacting with someone whose memory is in tatters it really is. If I have learned anything from living with Alzheimer’s, it’s that ultimately, we are all a collection of anecdotes – either of the things we can recall, or the stories we tell ourselves. So that recurring themes and phrases, once emblematic underpinnings of our ideas of self, can so easily end up floating around inside our heads junk code, like the agonising phrase in this story, Je t’aime pour toujours, Sylvie. I’ll always love you, Sylvie. (Even if I no longer know quite who, or where you are.)

It’s fair to say as I watched the short teaser Director Dan Clifton made for the film, I was already persuaded this was a project I would want to know more about.

Take a quick look now yourself, and I am sure you will feel the same.

Patient 39 Fundraiser from Dan Clifton on Vimeo.

|

MG: Starting with the most obvious thing I could think of, what made you choose ‘The Ghosts of a Bird’ to adapt? |

|

DAN CLIFTON: I came across the story almost by chance, not actively looking for something to film. I always really enjoy William Boyd anyway, and happened to pick Fascination [+link to book] up in the library. While reading ‘The Ghost of a Bird’ there was just something about this story, and the enigma of soldier with memory loss, that I found very interesting for several of reasons. The first was that it felt quite cinematic. The images in it are very strong, and I was quite drawn by that. There was something very clear about it. But more than this, like many William Boyd stories, it takes the form of a diary, and has a quiet, scientific tone, and I am very interested in these sorts of stories, and characters. It is very much this interest in scientists, and their outlooks, which informs not only Patient 39, but also an earlier film I made, called ‘The Calculus of Love’ and which starred Keith Allen. I’ve made a few documentary films about scientists and I am very interested in where the scientific imperative comes into conflict with human values. |

|

MG: That was something which really comes through with Keith Allen’s character in ‘The Calculus of Love’. The way he is utterly obsessed with his own research, but how ultimately it’s this obsession which ultimately destroyed him and everyone around him. |

|

DAN CLIFTON: Yes, well it seems to me we live in this culture which is completely colonised by the scientific view of things and yet somehow we know it doesn’t always quite measure up. So part of my interest in adapting ‘The Ghost of a Bird’ really went from there as well, and so I approached his agent about getting the rights. |

|

MG: Is it difficult to get the rights to do this sort of thing? |

|

DAN CLIFTON: It took a bit of persuading. But in our case, Boyd himself is a film-maker, and a writer and has spoken about the need to give breaks to short-story writers, so, (laughs) although I have not had any direct communication with him I feel his benign hand behind it. What I would say to other people in this position is if you don’t ask, you don’t get. |

|

MG: So how far into the process are you? Have you got a script and a storyboard? |

|

DAN CLIFTON: I started working on it last year, thinking about how I would go about it not just in terms of the ideas, but also how I would make the film. And by make the film, I actually mean fund the film. At the moment we have a fairly well-developed draft. The film-script is, of course, necessarily different than the short-story, but it also takes the form, at least initially, of the case notes of the doctor. But then, like the short story, it transitions to something a bit more personal, and the scientific tone changes as the relationship develops between the doctor and the patient. |

|

MG: Something which fascinated me in reading the story was the question of whose point-of-view you would stick with. In the ‘The Ghost of a Bird’ William Boyd sticks squarely in the POV of Doctor Moran, but I wondered if in retitling it as PATIENT 39 you were giving us an inkling that maybe we’d also see things from Gerald’s inner landscape? |

|

DAN CLIFTON: That’s something I did wrestle with, because the narrative is quite driven by this enigma of who Patient 39 is, and this draws you into the world of the film and the story. This did, in some ways, shift things away from Dr Moran, but I am very clear this is the doctor’s story. In the context of a short film you are always looking for a pivotal moment, or change, and the focus in this story I hope is how Dr Moran is changed by his relationship with Gerald Gault, or Patient 39, as we call him. For me, the interesting thing is that we see it all through Moran’s eyes, and how he meets this young man who, unlike him, is not a scientist, but a man who lives in his imagination, with a great sense of beauty and of nature, and who, because of his injury, lives in the moment. Moran, on the other hand, has never really seen the world this way, and so that is the exchange that takes place at the heart of the story. For Gault, although his memory loss means he no longer has all of the normal sorts of references we think of as going towards making up the self, his life is still very rich – and in some ways, perhaps even richer than Dr Moran’s – and that’s what interesting. |

|

MG: Would I be able to have a look at the script? |

|

DAN CLIFTON: No. I’d say, just don’t go there. (laughing) Or rather, sure. Why not? Once we’ve finished making the film. But as a filmmaker about to embark on this, what’s important at this point is to invite people to imagine the final film rather than get too caught up in what’s on the page. But once it’s done I’d be delighted to compare William Boyd’s story to my script to the finished film. |

|

MG: That could work too… I suppose the main reason I was asking is that, not being a script-writer, I am just dead curious to see how you plan to translate experiences which are so clearly ‘internal’ onto the screen. |

|

DAN CLIFTON: Interestingly enough, I think film is very good about telling these sorts of stories. I wrote a blog piece recently about amnesia in film, and how there is a long tradition of that. What film is very good at, because of the close-up perspective you don’t get in theatre, is in inviting us to access what is behind a person’s eyes, what’s going on in their head. Other people are a mystery to us, in some ways, but film allows us to examine that mystery. It allows us to create and enter a kind of heightened worlds, heightened states of sensory perception or distorted perception. Think for example of the treatment of heightened states through drug taking in film. There is a great cinematic tradition right there of how film can represent internal psychological states. So cinema has a long and distinguished tradition in this sense, and these are some of the things I’ve been thinking about in trying to portray the experience that Gault, the patient, has. |

|

MG: I was very struck by the tone of the fund-raising teaser you made – which I loved. I was wondering whether this overall mood is indicative of the sort of aesthetic feel we can expect to see in the finished film? |

|

DAN CLIFTON: To some extent yes. That’s the aspiration. To create an atmospheric, psychological tone, something very internalised, and of course, something that hopefully William Boyd will like in the end as well. |

So there you have it. The transition from ‘The Ghost of a Bird’ to ‘Patient 39’ is well under way, and it will be fascinating to see more about the project as it develops.

I certainly wouldn’t ask for your help so shamelessly if I were in any way involved in this production. But as this is my year of thinking about creativity, and I am deeply intrigued to see more of where Dan and his team at Atomium are going with this, I hope you’ll find it in your hearts, and more importantly your Paypal accounts, to send what you can!

I’m hoping to get down to the set when filming starts in March, and so will have more to tell you then.

I thought I had read everything by Boyd so am looking forward to reading this as well as seeing film. Cannot wait!

It’s one of the short stories in Fascination. Really interesting, and very Boyd. Draws on the idea of the journal, which he has used to such great effect elsewhere as well. Hope you enjoy it! I’ll look forward to hearing what you make of it if you get a chance to pop back. All the best, Melanie

[…] the crossover between medical and artistic narratives. Since this dovetails so neatly with what Dan Clifton said about his own interests in the original story, ‘The Ghost of a Bird’ I wanted to share it […]

I just had the pleasure of seeing the final results, the short film “Patient 39”. It was beautiful and insightful to the point you immediately become involved emotionally. Sylvie, every man has a Sylvie. The moment of innocence and love with purity. I can so easily understand why he longs to see her, especially after the horrors of war. The doctor who is so well portrayed gave us the moment of epiphany he had and the unique young man that Gearald, Patient 39, was and the treasures he possessed in a mind locked up by injury. I give this beautiful and so creative film five stars. View it on Shorts this February 2016.